What Was the Story Behind Thenidea of Culture and Style of Art of Renaissance People

Affiliate 3: The Renaissance

The Renaissance, significant "rebirth," was a period of innovation in culture, fine art, and learning that took place between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, starting in Italian republic and and then spreading to various other parts of Europe. It produced a number of artists, scientists, and thinkers who are still household names today: Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Donatello, Botticelli, and others. The Renaissance is justly famous for its achievements in art and learning, and even though some of its thinkers were somewhat conceited and off-base in dismissing the prior thousand years or and then as being zilch but the "Dark Ages," information technology is still the case that the Renaissance was enormously fruitful in terms of intellectual production and cosmos.

"The" Renaissance lasted from near 1300 – 1500. Information technology ended in the early sixteenth century in that its northern Italian heartland declined in economical importance and the pace of change and progress in the arts and learning slowed, but in a very real sense the Renaissance never truly ended – its innovations and advances had already spread across much of Europe, and even though Italy itself lost its prominence, the patterns that began in Italy continued elsewhere. That was true not only of fine art, simply of instruction, architecture, scholarship, and commercial practices.

The timing of the Renaissance coincided with some of the crises of the Middle Ages described in the last chapter. The overlap in dates is explained past the fact that well-nigh of Europe remained resolutely "medieval" during the Renaissance's heyday in Italia: the means of life, forms of technology, and political construction of the Middle Ages did not all of a sudden change with the flowering of the Renaissance, non least because it took then long for the innovations of the Renaissance to spread beyond Italy. As well, in Italy itself, the lives of most people (especially exterior of the major cities) were all but identical in 1500 to what they would accept been centuries before.

Groundwork

But put, the background of the Renaissance was the prosperity of northern Italy. Italia did not confront a major, ongoing series of wars like the Hundred Years' War in French republic. It was striking hard past the plague, but no more and so than most of the other regions of Europe. One unexpected "do good" to Italy was actually the Babylonian Captivity and Bully Western Schism: because the popes' potency was so express, the Italian cities found it like shooting fish in a barrel to operate with footling papal interference, and powerful Italian families oft intervened directly in the election of popes when information technology suited their interests. Also, the other powers of Europe either could non or had no involvement in troubling Italy: England and France were at war, the Holy Roman Empire was weak and fragmented, and Spain was not united until the tardily Renaissance period. In short, the crises of the Center Ages really benefited Italia, considering they were centered elsewhere.

In this relatively stable social and political environment, Italian republic besides enjoyed an advantage over much of the residual of Europe: it was far more than urbanized. Considering of its location as a crossroads between east and west, Italian cities were larger and there were merely more than of them as compared to other kingdoms and regions of Europe, with the concomitant economic prosperity and sophistication associated with urban life. By 1300, northern Italy boasted 20-three city-states with populations of 20,000 or more, each of which would take constituted an enormous city by medieval standards.

Italian cities, amassed in the north, represented almost 10% of Italy's overall population. While that means that 90% of the population was either rural or lived in pocket-size towns, at that place was still a far greater concentration of urban dwellers in Italia than anywhere else in Europe. Amid those cities were also several that boasted populations of over 100,000 by the fifteenth century, including Florence and Milan, which served as centers of banking, merchandise, and craftsmanship. Italian cities had large numbers of very productive arts and crafts guilds and workshops producing luxury goods that were highly desirable all over Europe.

Economics

Italy lay at the center of the lucrative merchandise between Europe and the Center Due east, a condition determined both by its geography and the part Italians had played in transporting goods and people during the crusading period. Forth with the trade itself, it was in Italy that central mercantile practices emerged for the commencement fourth dimension in Europe. From the Arab earth, Italian merchants learned virtually and ultimately adopted a number of commercial practices and techniques that helped them (Italians) stay at the forefront of the European economy as a whole. For example, Italian accountants adopted double-entry bookkeeping (accounts payable and accounts receivable) and Italian merchants invented the commenda, a way of spreading out the risk associated with business ventures amidst several partners – an early on form of insurance for expensive and risky commercial projects. Italian banks had agents all over Europe and provided reliable credit and bills of commutation, allowing merchants to travel around the entire Mediterranean region to trade without having to literally cart chests full of coins to pay for new wares.

1 other noteworthy innovation first employed in Europe past Italians was the apply of Arabic numerals instead of Roman numerals, since the former are so much easier to work with (eastward.thou. imagine trying to exercise complicated multiplication or sectionalization using Roman numerals similar "CLXVIII multiplied past XXXVIII," meaning "168 multiplied by 38" in Arabic numerals…information technology was simply far easier to innovate errors in adding using the quondam). Overall, Italian merchants, borrowing from their Arab and Turkic trading partners, pioneered efforts to rationalize and systematize business itself in order to get in more anticipated and reliable.

Benefiting from the fragmentation of the Church during the era of the Babylonian Captivity and the Great Western Schism, Italian bankers besides came to charge interest on loans, becoming the beginning Christians to defy the church's ban on "usury" in an ongoing, regular style. The stigma associated with usury remained, but bankers (including the Medici family that came to completely dominate Florentine politics in the fifteenth century) became so wealthy that social and religious stigma alone was non plenty to prevent the spread of the practise. This actually led to more anti-Semitism in Europe, since the one social role played by Jews that Christians had grudgingly tolerated – money-lending – was increasingly usurped by Christians.

Much of the prosperity of northern Italy was based on the trade ties (not simply mercantile practices) Italy maintained with the Middle East, which by the fourteenth century meant both the remains of the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople as well as the Ottoman Turkish empire, the rising power in the east. From the Turks, Italians (especially the keen mercantile empire controlled by Venice) bought precious cargo similar spices, silks, porcelain, and java, in return for European woolens, crafts, and bullion. The Italians were besides the go-betweens linking Asia and Europe by way of the Middle E: Italy was the European terminus of the Silk Road.

The Italian urban center-states were sites of manufacturing likewise. Raw wool from England and Spain made its manner to Italian republic to be processed into cloth, and Italian workshops produced luxury goods sought after everywhere else in Europe. Italian luxury goods were superior to those produced in the rest of Europe, and soon even Italian weapons were better-made. Italian farms were prosperous and, by the Renaissance period, produced a significant and ongoing surplus, feeding the growing cities.

1 consequence of the prosperity generated past Italian mercantile success was the rise of a culture of conspicuous consumption. Both members of the nobility and rich non-nobles spent lavishly to display their wealth too as their culture and learning. All of the famous Renaissance thinkers and artists were patronized by the rich, which was how the artists and scholars were able to concentrate on their work. In turn, patrons expected "their" artists to serve as symbols of cultural accomplishment that reflected well on the patron. The fluorescence of Renaissance art and learning was a outcome of that very specific use of wealth: mercantile and banking riches translated into social and political condition through art, compages, and scholarship.

Political Setting

Even though the western Roman Empire had fallen apart past 476 CE, the bang-up cities of Italy survived in better shape than Roman cities elsewhere in the empire. As well, the feudal organisation had never taken as hold as strongly in Italian republic – there were lords and vassals, but especially in the cities there was a large and strong independent class of artisans and merchants who aghast at subservience before lords, peculiarly lords who did not live in the cities. Thus, by 1200, most Italian cities were politically independent of lords and came to boss their respective hinterlands, serving as lords to "vassal" towns and villages for miles around.

Instead of kings and vassals, power was in the hands of the popoli grossi, literally significant the "fat people," just here meaning simply the rich, noble and non-noble alike. Nigh 5% of the population in the richest cities was amongst them. The culture of the popoli grossi was rife with flattery, backstabbing, and politicking, since and then much depended on personal connections. Since noble titles meant less, more depended on i'south family reputation, and the near of import thing to the social aristocracy was accolade. Whatsoever perceived insult had to be met with retaliation, significant there was a great bargain of bloodshed betwixt powerful families – Shakespeare'due south famous play Romeo and Juliet is set in Renaissance Italy, featuring rival elite families locked in a blood feud over honor. There was no such thing equally a law forcefulness, after all, just the guards of the rich and powerful and, normally, a city guard that answered to the city council. The latter was oftentimes controlled by powerful families on those councils, however, so both law enforcement and personal vendettas were generally carried out past individual mercenaries.

Another aspect of the identify of the popoli grossi was that, despite their penchant for feuds, they required a peaceful political setting on a large calibration in order for their commercial interests to prosper. Thus, they were often hesitant to embark on big-calibration war in Italia itself.

Likewise, the focus on education and culture that translated direct into the cosmos of Renaissance fine art and scholarship was tied to the identity of the popoli grossi equally people of peace: elsewhere in Europe noble identity was still very much associated with war, whereas the popoli grossi of Italy wanted to show off both their mastery of arms and their mastery of thought (along with their good gustation).

Portrait of a young Cosimo de Medici, who would become the de facto ruler of Florence in the fifteenth century. He is depicted belongings a book and wearing a sword: symbols of his learning and his say-so.

The central irony of the prosperity of the Renaissance was that even in northern Italy, the vast majority of the population benefited only indirectly or not at all. While the lot of Italian peasants was not significantly worse than that of peasants elsewhere, poor townsfolk had to endure heavy taxes on basic foodstuffs that fabricated it especially miserable to be poor in 1 of the richest places in Europe at the time. A significant percentage of the population of cities were "paupers," the indigent and homeless who tried to scrape past equally laborers or sought charity from the Church building. Cities were especially vulnerable to epidemics as well, adding to the misery of urban life for the poor.

The Dandy City-States of the Renaissance

In the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth centuries, the city-states of northern Italy were aggressive rivals; well-nigh of the formerly-independent cities were swallowed upwardly by the most powerful amidst them. Withal, as the power of the French monarchy grew in the west and the Ottoman Turks became an active threat in the east, the about powerful cities signed a treaty, the Peace of Lodi, in 1454 which committed each city to the defense of the existing political order. For the next 40 years, Italy avoided major conflicts, a catamenia that coincided with the height of the Renaissance.

The nifty city-states of this period were Milan, Venice, and Florence. Milan was the archetypal despot-controlled urban center-state, reaching its height under the Visconti family from 1277 – 1447. Milan controlled considerable merchandise from Italia to the north. Its wealth was dwarfed, notwithstanding, by that of Venice.

Venice

Venice was ruled past a merchant quango headed by an elected official, the Doge. Its Mediterranean empire generated so much wealth that Venice minted more gold currency than did England and France combined, and its gold coins (ducats) were ever exactly the same weight and purity and were accustomed across the Mediterranean as a result. Its authorities had representation for all of the moneyed classes, just no 1 represented the majority of the city's population that consisted of the urban poor.

The main source of Venice'southward prosperity was its control of the spice trade. It is difficult to overstate the value of spices during the Middle Ages and Renaissance – Europeans had a limitless hunger for spices (every bit an aside, note that the theory that spices were desirable because they masked the taste of rotten meat is plainly simulated; medieval and Renaissance-era Europeans did not eat spoiled food). Unlike other luxury goods that could exist produced in Europe itself, spices could only be grown in the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, meaning their transportation to European markets required voyages of many thousands of miles, vastly driving up costs.

The European terminus of much of that trade was Venice. In nigh 1300 40% of all ships bearing spices offloaded in Venice, and past 1500 it was up to lx%. The prices allowable by spices ensured that Venetian merchants could achieve incredible wealth. For example, nutmeg (grown in Republic of indonesia, halfway around the world from Italian republic) was worth a total 60,000% of its original price once information technology reached Europe. Likewise, spices like pepper, cloves, and cinnamon could merely be imported rather than grown in Europe, and Venice controlled the majority of that hugely lucrative trade. Spices were, in so many words, worth far more than their weight in gold.

Based on that wealth, Venice was the outset place to create true banks (named later on the desks, banchi, where people met to exchange or borrow coin in Venice). Furthermore, innovations like the letter of the alphabet of credit were necessitated by Venice's remoteness from many of its trade partners; it was as well risky to travel with chests full of aureate, so Venetian banks were the showtime to piece of work with letters of credit between branches. A letter of credit could be issued from 1 banking company branch at a sure amount, redeemable only by the business relationship owner. That private could and so travel to any metropolis with a Venetian bank branch and redeem the letter of the alphabet of credit, which could then be spent on trade appurtenances.

In improver, because Venice needed a peaceful merchandise network for its continuing prosperity, it was the start ability in Europe to rely heavily on formal diplomacy in its relations with neighboring states. By the late 1400s practically every regal court in Europe, the Middle East, and Northward Africa had a Venetian ambassador in residence. The overall result was that Venice spearheaded many of the practices and patterns that later spread across northern Italy and, ultimately, to the residuum of Europe: the political ability of merchants, advanced banking and mercantile practices, and a sophisticated international diplomatic network.

Florence and Rome

Florence was a republic with longstanding traditions of civic governance. Citizens voted on laws and served in official posts for set terms, with powerful families dominating the system. Past 1434 the real power was in the hands of the Medici family unit, who controlled the metropolis authorities (the Signoria) and patronized the arts. Rising from obscurity from a resolutely non-noble background, the Medici eventually became the official bankers to the papacy, acquiring vast wealth as a issue. The Medici spent huge sums on the city itself, funding the creation of churches, orphanages, municipal buildings, and the completion of the great dome of the city'southward cathedral, at the time the largest freestanding dome in Europe. They also patronized well-nigh of the most famous Renaissance artists (at the fourth dimension as well as in the nowadays), including Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo.

Florence benefited from a strong culture of didactics, with Florentines priding themselves not just on wealth, just noesis and refinement. By the fifteenth century at that place were 8,000 children in both religious and civic schools out of a population of 100,000. Florentines boasted that even their laborers could quote the neat poet, and native of Florence, Dante Alighieri (author of The Divine Comedy). At the height of Medici, and Florentine, power in the 2nd one-half of the fifteenth century, Florence was unquestionably the leading urban center in all of Italy in terms of fine art and scholarship. That key position diminished past about 1500 as foreign invasions undermined Florentine independence.

The city of Rome, nonetheless, remained firmly in papal control despite the decline in independence of the other major Italian cities, having go a major Renaissance city afterward the stop of the Great Western Schism. The popes re-asserted their command of the Papal States in central Italia, in some cases (like those of Julius Two, r. 1503 – 1513) personally taking to the battlefield to atomic number 82 troops against the armies of both strange invaders and rival Italians. The popes ordinarily proved effective at secular rule, only their spiritual leadership was undermined by their tendency to live like kings rather than priests; the most notorious, Alexander Half dozen (r. 1492 – 1503), sponsored his children (the infamous Borgia family) in their attempts to seize territory all across northern Italy. Thus, fifty-fifty when "expert popes" came along occasionally, the overall design was that the popes did fairly petty to reinforce the spiritual potency they had already lost because of the Nifty Western Schism

Regardless of their moral failings, the popes restored Rome to importance every bit a city after information technology had fallen to a population of fewer than 25,000 during the Babylonian Captivity. Nether the so-called "Renaissance popes," the Vatican itself became the gloriously decorated spectacle that it is today. Julius 2 paid Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, and many of the other famous works of Renaissance artists stud the walls and facades of Vatican buildings. In brusque, popes subsequently the finish of the Smashing Western Schism were often much more focused on behaving like members of the popoli grossi, fighting for power and honor and patronizing great works of fine art and architecture, rather than worrying well-nigh the spiritual authority of the Church to laypeople.

In full general, the Renaissance did not coincide with a great period of technological advances. As with all of pre-mod history, the step of technological alter during the Renaissance period was glacially slow by contemporary standards. There was one momentous exception, withal: the proliferation of the movable-type printing press. Not until the invention of the typewriter in the late nineteenth century and the Internet in the tardily twentieth century would comparable changes to the diffusion of data come almost. Print vastly increased the rate at which information could be shared, and in plow, information technology underwrote the rise in literacy of the early on modern period. It moved the production of text in Europe away from a "scribal" tradition in which educated people manus-copied of import texts toward a system of mass-production.

In the centuries leading up to the Renaissance, of grade, in that location had been some major technological advances. The agronomical revolution of the high Heart Ages had been brought about by engineering (heavier plows, new harnesses, crop rotation, etc.). Likewise, changes in warfare were increasingly tied to armed services engineering science: first the introduction of the stirrup, and then everything associated with a "gunpowder revolution" that began in earnest in the fifteenth century (described in a subsequent chapter). Print, withal, introduced a revolution in ideas. Past making the distribution of information fast and comparatively cheap, more people had admission to that information than ever earlier. Print was too an enormous leap forward in the long-term view of human engineering as a whole, since the scribal tradition had been in place since the creation of writing itself.

The printing press works past blanket a iii-dimensional impression of an image or text with ink, and then pressing that ink onto newspaper. The concept had existed for centuries, outset invented in China and used likewise in Korea and parts of Central Asia, but at that place is no prove that the concept was transmitted from Asia to Europe (information technology might have, but at that place is only no proof either way). In the late 1440s, a High german goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg from the city of Meinz struck on the thought of carving individual letters into pocket-sized, movable blocks of wood (or casting them in metal) that could be rearranged as necessary to create words. That innovation, known as movable type, made it feasible to print non just a single page of text, merely to simply rearrange the letters to print subsequent pages. With movable type, an entire book could be printed with clear, readable letters, and at a fraction of the price of manus-copying.

A mod replica of a printing press of Gutenberg's era.

Gutenberg himself pioneered the European version of the press process. After developing a working prototype, he created the first true printed volume to achieve a mass market, namely a copy of the Latin Vulgate (the official version of the Bible used by the Church building). Later dubbed the "Gutenberg Bible," it became available for purchase in 1455 and in turn became the globe'south first "best-seller." One reward it possessed over hand-written copies of the Bible that chop-chop became apparent to church building officials was that errors in the text were far less likely to be introduced as compared to hand-copying. Likewise, once new presses were built in cities and towns outside of Meinz, it became cheaper to purchase a printed Bible than i written in the scribal tradition.

Print spread apace. Within about twenty years there were printing presses in all of the major cities in Western and Southern Europe. Gutenberg personally trained apprentice printers, who became highly sought-later in cities everywhere once the benefits of impress became apparent. By 1500, about 50 years after its invention, the printing press had already largely replaced the scribal tradition in volume production (there was a notable lengthy delay in its diffusion to Eastern Europe, especially Russia, however – it took until 1552 for a printing to come to Russia). Presses tended to operate in big cities and smaller contained cities, particularly in the Holy Roman Empire. The complimentary cities of the High german lands and Italian republic were thus every bit likely to host a press equally were larger capital cities like Paris and Rome.

Gutenberg would go on to invent printed illustration in 1461, using carved blocks that were sized to fit alongside movable type. Printed illustration became crucial to the improvidence of information because literacy rates remained depression overall; fifty-fifty when people could not read, however, they could look at pamphlets and posters (called "broadsides") with illustrations. Mere decades after the invention of the press, inexpensive printed posters and pamphlets were commonplace in the major cities and towns, often shared and read aloud in public gatherings and taverns. Thus, even the illiterate enjoyed an increased admission to information with print.

Printing had diverse, and enormous, consequences. Information could exist disseminated far more speedily than ever before. Whereas with the scribal tradition, readers tended to hold books in reverence, with the reader having to seek out the book, now books could get to readers. In plough, at that place was a existent incentive for all reasonably prosperous people to learn to read because they now had access to meaningful texts at a relatively affordable price. While religious texts dominated early print, both literary works and political commentaries followed. Overall, print led to a revolutionary increase in the sheer volume of all kinds of written material: in the first fifty years after the invention of the press, more than books were printed than had been copied in Europe past manus since the fall of Rome.

Non all writing shifted to print, still. A scribal tradition connected in the production of official documents and luxury items. Too, personal correspondence and business organisation transactions remained manus-written, with the legacy of good penmanship surviving well into the twentieth century (in part because information technology was not until the typewriter was invented in the nineteenth century that printed documents could be produced ad hoc). Nonetheless, by the late fifteenth century, whenever a text could exist printed to serve a political purpose or to generate a profit, information technology well-nigh certainly would exist.

In that location were other, unanticipated, issues that arose because of print. In the by, while the Church did its best to cleft down on heresies, it was not necessary to impose any kind of formal censorship. No written textile could be mass-produced, so the just ideas that spread chop-chop did then through word of mouth. Print made censorship both much more hard and much more of import, since at present anyone could impress just about annihilation. Every bit early on as the 1460s, print introduced confusing ideas in the course of the next all-time-seller to follow the Bible itself, a work that advocated the pursuit of salvation without reference to the Church entitled The Imitation of Christ. The Church would eventually (in 1571) introduce an official Alphabetize of Prohibited Books, merely several works were already banned by the time the Index was created.

While there were other effects of print, one bears item annotation: it began the process of standardizing language itself. The long, slow shift from a vast panoply of vernacular dialects across Europe to a set of accepted and official languages was incommunicable without print. Print necessitated that standardization, and so that people in different parts of "France" or "England" were able to read the same works and understand their grammar and their meaning. For the first time, the very concept of proper spelling emerged, and existing ideas about grammer began the process of standardization likewise.

Patronage

The most memorable, or at least iconic, furnishings of the Renaissance were artistic. To understand why the Renaissance brought near such a remarkable explosion of art, it is crucial to grasp the nature of patronage. In patronage, a member of the popoli grossi would pay an artist in advance for a work of fine art. That work of art would be displayed publicly – about obviously in the case of architecture with the beautiful churches, orphanages, and municipal buildings that spread beyond Italian republic during the Renaissance. In turn, that art would attract political power and influence to the person or family who had paid for it because of the laurels associated with funding the best artists and beingness associated with their work. While there was plenty of bloodshed between powerful Renaissance families, their political competition as often took the form of an ongoing boxing over who could committee the best art then "requite" that art to their habitation city, rather than actual fighting in the streets.

Mayhap the near spectacular example of patronage in action was when Cosimo de Medici, and then the leader of the Medici family unit and its vast cyberbanking empire, threw a city-broad political party called the Council of Florence in 1439. The Council featured public lectures on Greek philosophy, displays of art, and a huge church council that brought together representatives of both the Latin Church building and the Eastern Orthodox Church building in a (doomed) attempt to heal the schism that divided Christianity. The Catholic hierarchy besides used the occasion to establish the canonical and in a sense "final" version of the Christian Bible itself (in question were which books ought to be included in the Old Attestation). The entire matter was paid by Cosimo out of his personal fortune – he fifty-fifty paid for the travel expenses of visiting dignitaries from places every bit far abroad as Bharat and Ethiopia. The Quango clinched the Medici equally the family of Florence for the next generation, with Cosimo being described by a gimmicky as a "king in all just name."

Art and learning benefited enormously from the wealth of northern Italy precisely considering the wealthy and powerful of northern Italia competed to pay for the best art and the most innovative scholarship – without that course of cultural and political contest, it is hundred-to-one that many of the masterpieces of Renaissance fine art would have e'er been created.

Humanism

The starting betoken with studying the intellectual and artistic achievements of the Renaissance is recognizing what the word ways: rebirth. But what was beingness reborn? The answer is the culture and ideas of classical Europe, namely ancient Greece and Rome. Renaissance thinkers and artists very consciously fabricated the claim that they were reviving long-lost traditions from the classical world in areas as diverse as scholarship, poetry, architecture, and sculpture. The feeling among most Renaissance thinkers and artists was that the ancient Greeks and Romans had achieved truly incredible things, things that had non been, and peradventure could never exist, surpassed. Much of the Renaissance began equally an attempt to mimic or copy Greek and Roman art and scholarship (correspondence in classical Latin, for case), but over the decades the more outstanding Renaissance thinkers struck out on new paths of their own – still inspired by the classics, but seeking to be creators in their own correct too.

Of the various themes of Renaissance thought, perhaps the most important was humanism, an ancient intellectual prototype that emphasized both the beauty and the centrality of humankind in the universe. Humanists held that humankind was inherently rational, cute, and noble, rather than debased, wicked, or weak. They sought to celebrate the beauty of the man body in their art, of the human being mind and human achievements in their scholarship, and of human society in the elegance of their architectural pattern. Humanism was, amidst other things, an optimistic attitude toward creative and intellectual possibility that cited the achievements of the aboriginal globe as proof that humankind was the crowning achievement of God's cosmos.

Renaissance humanism was the root of some very modern notions of individuality, along with the idea that education ought to arrive at a well-rounded individual. The goal of teaching in the Renaissance was to realize as much of the human potential as possible with a robust teaching in various disciplines. This was a true, meaningful change over medieval forms of learning in that education's major purpose was no longer believed to exist the description of religious questions or better intellectual support for religious orthodoxy; the point of educational activity was to create a more competent and well-rounded person instead.

Forth with the idea of a well-rounded private, Renaissance thinkers championed the idea of civic humanism: one's moral and upstanding standing was tied to devotion to i'south city. This was a Greek and Roman concept that the not bad Renaissance thinker Petrarch championed in detail. Here, the Medici of Florence are the ultimate case: there was a tremendous endeavour on the part of the rich and powerful to invest in the urban center in the form of building projects and art. This was tied to the prestige of the family, of course, but information technology was also a heartfelt dedication to one's home, analogous to the present-day concept of patriotism.

Practically speaking, there was a shift in the practical business of teaching from medieval scholasticism, which focused on law, medicine, and theology, to disciplines related to business and politics. Princes and other elites wanted skilled bureaucrats to staff their merchant empires; they needed literate men with a knowledge of law and mathematics, even if they themselves were not merchants. Metropolis governments began educating children (girls and boys alike, at least in certain cities like Florence) directly, along with the role played by individual tutors. These schools and tutors emphasized practical education: rhetoric, math, and history. Thus, one of the major furnishings of the Italian Renaissance was that this new form of teaching, usually referred to as "humanistic education" spread from Italy to the rest of Europe past the late fifteenth century. By the sixteenth century, a broad cantankerous-section of European elites, including nobles, merchants, and priests, were educated in the humanistic tradition.

A "Renaissance man" (notation that in that location were of import women thinkers too, but the term "Renaissance human being" was used exclusively for men) was a human who cultivated classical virtues, which were not quite the same every bit Christian ones: understanding, benignancy, compassion, fortitude, judgment, eloquence, and honor, among others. Drawing from the piece of work of thinkers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Virgil, Renaissance thinkers came to support the idea of a virtuous life that was not the same thing as a specifically Christian virtuous life. And, importantly, it was possible to get a good person just through studying the classics – all of the major figures of the Renaissance were Christians, simply they insisted that 1's moral status could and should exist shaped past emulation of the ancient virtues, combined with Christian piety. While the Renaissance example for the debasement of medieval civilisation was overstated (medieval intellectual life prospered during the late Middle Ages) there was definitely a distinct kind of intellectual courage and optimism that came out of the return to classical models over medieval ones during the Renaissance.

1 of import caveat must exist included in discussing humanistic pedagogy, withal. While well-nigh male humanists supported didactics for girls, they insisted that it was to be very different than that offered to boys. Girls were to read specific texts drawn from the Bible, the "Church Fathers" (of import theologians in the early on history of the Church), and from classical Greek and Roman writers that emphasized morality, modesty, and obedience. An educated girl was trained to exist an obedient, companionable wife, non an independent thinker in her own right. That theme would remain in identify in the male-dominated realm of education in Europe for centuries to come, although it is clear from the number of independent, intellectually courageous women writers throughout the early on modern period that girls' education did non always succeed in creating compliant, deferential women in the stop.

Too, humanism contributed to an important, ongoing public debate that lasted for centuries: the querelles des femmes ("debates virtually women"). Between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries various intellectuals in universities, churches, and aloof courts and salons wrote numerous essays and books contesting whether or not women were naturally immoral, weak, and foolish, or if instead education and environment could lead to intelligence and morality comparable with those of men. While men had dominated these debates early on on, women educated in the humanist tradition joined in the querelles in earnest during the Renaissance, arguing both that pedagogy was key to elevating women'southward competence and that women shared precisely the same spiritual and moral nature every bit did men. Unfortunately, while a significant minority of male thinkers came to concur, most remained determined that women were biologically and spiritually inferior, destined for their traditional roles and ill-served by advanced education.

Important Thinkers

The Renaissance is remembered primarily for its great thinkers and artists, with some exceptional individuals (similar Leonardo da Vinci) being renowned as both. What Renaissance thinkers had in mutual was that they embraced the ideals of humanism and used humanism as their inspiration for creating innovative new approaches to philosophy, philology (the study of language), theology, history, and political theory. In other words, reading the classics inspired Renaissance thinkers to emulate the great writers and philosophers of aboriginal Greece and Rome, creating poesy, philosophy, and theory on par with that of an Aristotle or a Cicero. Some of the almost noteworthy included the following.

Dante (1265 – 1321)

Durante degli Alighieri, meliorate remembered but every bit Dante, was a major figure who anticipated the Renaissance rather than existence alive during nigh of it (while there is no "official" starting time to the Renaissance, the life of Petrarch, described below, lends itself to using 1300 as a convenient appointment). Experiencing what would later be called a mid-life crunch, Dante turned to poetry to console himself, ultimately producing the greatest written piece of work of the belatedly Middle Ages: The Divine Comedy. Written in his own native dialect, the Tuscan of the city of Florence, The Divine Comedy describes Dante's descent into hell, guided past the spirit of the classical Roman poet Virgil. Dante and Virgil sally on the other side of the earth, with Dante ascending the mountain of purgatory and ultimately entering heaven, where he enters into the divine presence.

Dante'south piece of work, which soon became justly famous in Italy and so elsewhere in Europe, presaged some of the essential themes of Renaissance idea. Dante's travels through hell, purgatory, and sky in the poem are replete with encounters with 2 categories of people: Italians of Dante'south lifetime or the recent past, and both real and mythical figures from ancient Greece and Rome. In other words, Dante was indifferent to the entire menstruation of the Centre Ages, concentrating instead on what he imagined the spiritual fate of the great thinkers and heroes of the classical historic period would have been (and gleefully relegating Italians he hated to infernal torments). Ultimately, his work became and then famous that it established Tuscan every bit the basis of what would somewhen become the language of "Italian" – all educated people in Italia would somewhen come to read the Comedy as a matter of course and information technology came to serve as the founding document of the modern Italian language in the process.

Petrarch (1304 – 1374)

Francesco Petrarca, known as Petrarch in English language, was in many ways the founding male parent of the Renaissance. Like Dante, he was a Florentine (native of the city of Florence) and single-handedly spearheaded the exercise of studying and imitating the corking writers and thinkers of the past. Petrarch personally rediscovered long-lost works past Cicero, widely considered the greatest writer of ancient Rome during the republican flow, and prepare well-nigh training himself to emulate Cicero's rhetorical fashion. Petrarch wrote to friends and assembly in a classical, grammatically spotless Latin (as opposed to the oftentimes sloppy and error-ridden Latin of the Middle Ages) and encouraged them to learn to emulate the classics in their writing, idea, and values. He went on to write many works of poetry and prose that were based on the model provided by Cicero and other ancient writers.

Petrarch was responsible for coming upward with the very idea of the "Dark Ages" that had separated his ain era from the greatness of the classical past. His own poetry and writings became so pop among other educated people that he deserves a great deal of personal credit for sparking the Renaissance itself; post-obit Petrarch, the idea that the classical world might be "reborn" in northern Italy acquired a great deal of popularity and cultural forcefulness.

Christine de Pizan (1364 – 1430)

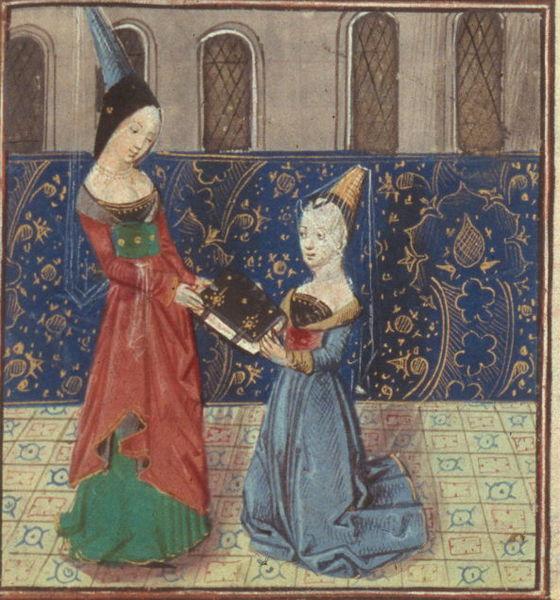

Christine de Pizan was the most famous and important adult female thinker and writer of the Renaissance era. Her begetter, the court astrologer of the French male monarch Charles 5, was infrequent in that he felt it important that his daughter receive the same quality of education afforded to aristocracy men at the fourth dimension. She went on to become a famous poet and author in her own correct, beingness patronized (i.e. receiving commissions for her writing) by a wide diverseness of French and Italian nobles. Her best-known work was The Book of the Urban center of Ladies, in which she attacked the and then-universal thought that women were naturally unintelligent, sinful, and irrational; it was a cardinal text in the querelles des femmes noted higher up. Instead, she argued, history provided a vast catalog of women who had been moral, pious, intelligent, and competent, and that information technology was men'southward pride and the refusal of men to allow women to be properly educated that held women back. In many ways, the City of Ladies was the first truly feminist work in European history, and it is striking that she was supported by, and listened to by, elite men due to her obvious intellectual gifts despite their own deep-seated sexism.

In the analogy above, Christine de Pizan presents a copy of The City of Ladies to a French noblewoman, Margaret of Burgundy. The illustration itself is in the pre-Renaissance "Gothic" way, without linear perspective, despite its approximate date of 1475. This is i example of the relatively slow spread of Renaissance-inspired artistic innovations.

Desiderius Erasmus (1466 – 1536)

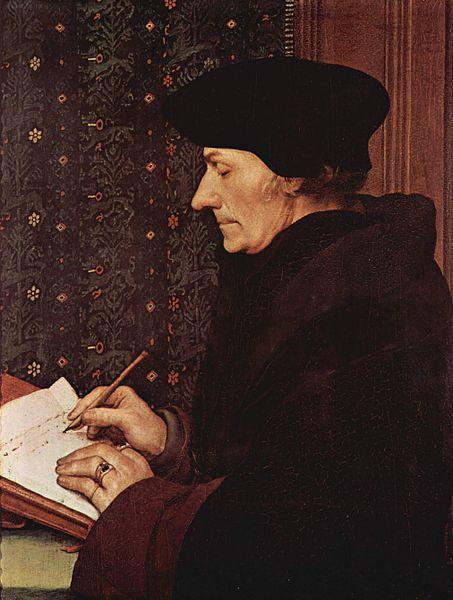

Erasmus was an astonishingly erudite priest who benefited from both the traditional scholastic education of the late-medieval church building and the new humanistic style that emerged from the Renaissance. Of his various talents, one of the nearly of import was his mastery of philology: the history of languages. Erasmus became completely fluent not only in classical and medieval Latin, merely in the Greek of the New Attestation (i.e. most of the primeval versions of the New Attestation of the Bible are written in the vernacular Greek of the first century CE). He also became conversant in Hebrew, which was very uncommon among Christians at the fourth dimension.

In the higher up well-known portrait of Erasmus, he is depicted in heavy, fur-lined robes and lid, a necessity fifty-fifty when indoors in Northern Europe for much of the year. Realistic portraiture was another major innovation of the Renaissance period.

Armed with his lingual virtuosity, Erasmus undertook a vast report and re-translation of the New Attestation, working from various versions of the Greek originals and correcting the Latin Vulgate that was the most widely used version at the time. In the process, Erasmus corrected the New Testament itself, catching and fixing numerous translation errors (while he did not re-translate the Old Testament from the Hebrew, he did point out errors in it every bit well).

Erasmus was criticized by some of his superiors within the Church because he was not officially authorized to conduct out his studies and translations; nonetheless, he ended up producing an extensively notated re-translation of the New Testament with numerous corrections. Chiefly, these corrections were not just a question of grammatical problems, but of meaning. The Christian message that emerged from the "correct" version of the New Attestation was a deeply personal philosophy of prayer, devotion, and morality that did non correspond to many of the structures and practices of the Latin Church. He was as well an abet of translations of the Bible into colloquial languages, although he did not produce such a translation himself.

Some of his other works other included In Praise of Folly, a satirical set on on abuse inside the church, and Handbook of the Christian Soldier, which de-emphasized the importance of the sacraments. Erasmus used his abundant wit to ridicule sterile medieval-manner scholastic scholars, the corruption of "Christian" rulers who were substantially glorified warlords, and even the very thought of witches, which he demonstrated relied on a faulty translation from the Hebrew of the Onetime Attestation.

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469 – 1527)

Machiavelli was a "courtier," a professional politician, ambassador, and official who spent his life in the courtroom of a ruler – in his case, as part of the city authorities of his native Florence. While in Florence, Machiavelli wrote various works on politics, most notably a consideration of the proper functioning of a republic like Florence itself. Unfortunately for him, Machiavelli was caught up in the whirlwind of power politics at court and ended upwardly being exiled by the Medici.

While in exile, Machiavelli undertook a new piece of work of political theory which he titled The Prince. Here, Machiavelli detailed how an constructive ruler should behave: training constantly in war, forcing his subjects to fear (merely not hate) him, studying the ancient past for role models like Alexander the Slap-up and Julius Caesar, and never wasting a moment worrying near morality when power was on the line. In the process, Machiavelli created what was arguably the first work of "political scientific discipline" that abandoned the moralistic arroyo of how a ruler should comport as a proficient Christian and instead embraced a practical guide to holding power. He dedicated the piece of work to the Medici in hopes that he would be allowed to return from exile (he detested the rural bumpkins he lived amidst in exile and longed to return to cosmopolitan Florence). Instead, The Prince caused a scandal when it came out for completely ignoring the role of God and Christian morality in politics, and Machiavelli died not long afterwards. That existence noted, Machiavelli is now remembered as a pioneering political thinker. Information technology is rubber to assume that far more rulers accept consulted The Prince for ideas of how to maintain their power over the years than 1 of the moralistic tracts that was preferred during Machiavelli's lifetime.

Baldassarre Castiglione (1478 – 1529)

Castiglione was the author of The Courtier, published at the end of his life in 1528. Whereas Machiavelli's The Prince was a applied guide for rulers, The Courtier was a guide to the nobles, wealthy merchants, high-ranking members of the Church, and other social elites who served and schemed in the courts of princes: courtiers. The piece of work centered on what was needed to win the prince's favor and to influence him, not just avoiding embarrassment at courtroom. This was tied to the growing sense of what information technology was to be "civilized" – Italians at the fourth dimension were renowned across Europe for their refinement, the quality of their clothes and jewelry, their wit in conversation, and their good taste. The relatively crude tastes of the dignity of the Middle Ages were "revised" starting in Italy, with Castiglione serving as both a symptom and cause of this shift.

The effective courtier, according to Castiglione, was tasteful, educated, clever, and subtle in his actions and words, a truthful politician rather than merely a warrior who happened to have inherited some land. Going forward, growing numbers of political elites came to resemble a Castiglione-fashion courtier instead of a thuggish medieval knight or "man-at-artillery." When he died, no less a personage than the Holy Roman Emperor Charles 5 lamented his loss and paid tribute to his retentivity.

Art and Artists

Mayhap the most iconic aspect of the Renaissance as a whole is its tremendous artistic achievements – figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti are household names in a style that Petrarch is not, despite the fact that Petrarch should be credited for creating the very concept of the Renaissance. The fame of Renaissance art is thanks to the incredible inventiveness of the great Renaissance artists themselves, who both imitated classical models of art and ultimately forged entirely new artistic paths of their own.

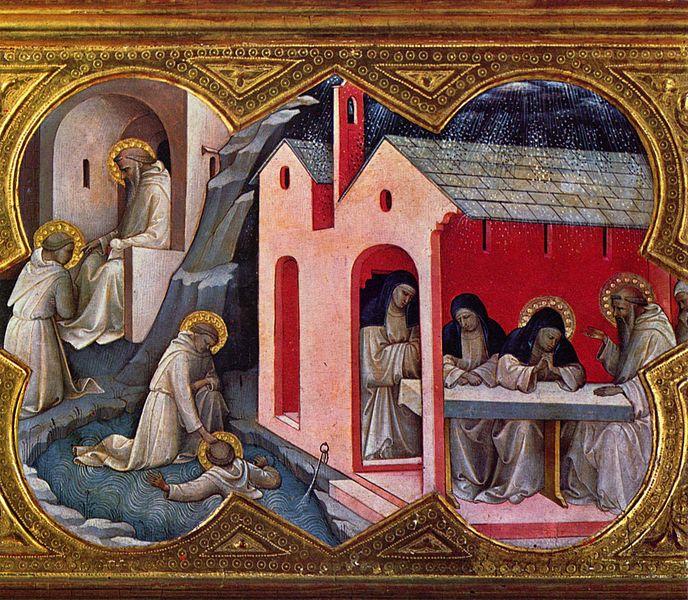

Medieval fine art (chosen "Gothic" after 1 of the Germanic tribes that had conquered the Roman Empire) had been unconcerned with realistic depictions of objects or people. Medieval paintings often presented things from several angles at once to the viewer and had no sense of 3-dimensional perspective. Likewise, Gothic architecture tended to exist beefy and overwhelming rather than refined and frail; the great examples of Gothic architecture are undoubtedly the cathedrals built during the Middle Ages, often beautiful and inspiring but a far cry from the symmetrical, airy structures of aboriginal Greece and Rome.

Another example of Gothic art. The artist, Lorenzo Monaco, painted during the Renaissance period, but the piece of work was created before linear perspective had replaced the "two-dimensional" style of Gothic painting.

In contrast, Renaissance artists studied and copied ancient frescoes and statues in an attempt to learn how to realistically describe people and objects. And, just as Petrarch "invented" the major themes of Renaissance thought past imitating and championing classical humanist thought, a Florentine artist, builder, and engineer named Filippo Brunelleschi "invented" Renaissance art through the imitation of the classical earth.

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 1446)

Brunelleschi was an astonishing creative and applied science genius. He became a prominent customer of the Medici, and with their political and financial support he undertook the structure of what would exist the largest free-continuing domed structure in all of Europe: the dome of the cathedral of Florence. For generations, the cathedral of Florence had stood unfinished, its primary tower having been built too large and besides tall for any architect to consummate. Literally no one knew how to build a freestanding stone dome on pinnacle of a tower over 350 feet loftier. By studying ancient Roman structures and employing his own incredible intellect, Brunelleschi built the dome in such a way that information technology held its internal construction together during the structure process. He invented a giant, geared winch to raise huge blocks of sandstone hundreds of feet in the air and was even known to personally ascend the structure to place bricks. The dome was completed in 1413, crowning both his fame every bit an architect and the Medici's role every bit the greatest patrons of Renaissance art and compages at the time.

Gimmicky photograph of the Florence Cathedral, with Brunelleschi's dome on the correct.

While the dome is ordinarily considered Brunelleschi's greatest accomplishment, he was likewise the (re-)inventor of one of the most important artistic concepts in history: linear perspective. He was the first person in the Western globe to make up one's mind how to draw objects in ii dimensions, on a piece of paper or the equivalent, in such a manner that they looked realistically three-dimensional (i.e. having depth, as in looking off into the distance and seeing objects that are farther away "expect smaller" than those nearby). Here, Brunelleschi was unquestionably influenced by a medieval Arab thinker, Ibn al-Haytham, whose Volume of Eyes laid out theories of light and sight perception that described linear perspective. The Volume of Eyes was bachelor to Brunelleschi in Latin translation, and, crucially, Brunelleschi applied the concept of perspective to actual art (which al-Haytham had not, focusing instead on the scientific footing of optics). In doing and so, Brunelleschi introduced the ability for artists to create realistic depictions of their subjects. This innovation spread rapidly and completely revolutionized the visual arts, resulting in far more lifelike drawings and paintings.

Sandro Botticelli (1445 – 1510)

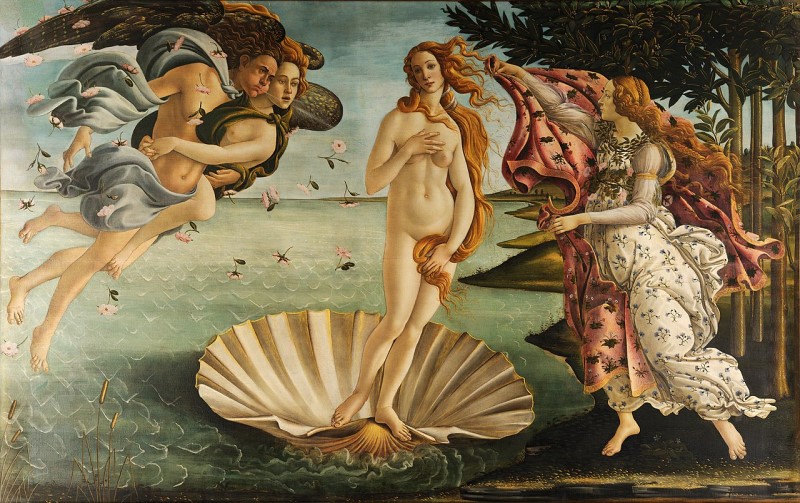

Botticelli exemplified the life of a successful Renaissance painter during the acme of the virtually productive artistic period in Florence and Rome. Likewise, his works focused on themes cardinal to the Renaissance as a whole: the importance of patronage, the celebration of classical figures and ideas, the beauty of the human body and mind, and Christian piety. Botticelli was patronized by various members of the Florentine popolo grossi, past the Medici, and by popes, producing numerous frescos (wall paintings done on plaster), portraits, and both biblical and classical scenes. Two of his virtually famous works capture dissimilar aspects of Renaissance art:

The Adoration of the Magi (1475), above, depicts members of the Medici family, Botticelli's patrons, as taking part in 1 of the key scenes from the birth of Christ. Botticelli even included himself in the painting; his cocky-portrait is the figure on the far correct. Note how all of the figures are dressed equally wealthy Italians of the fifteenth century, not Jews, Romans, and Persians of the first century. Despite the abundance of biblical scenes in Renaissance painting, no attempt was fabricated to depict people as they might have appeared at the time. Instead, the paintings projected the world of the popoli grossi back in time, sometimes (as with this example) even including portraits of actual important Italians.

The Nascency of Venus (1485) celebrates a primal moment in Greek mythology when the goddess of dear, sexuality, and dazzler is born from the bounding main. Here Botticelli pushed the boundaries of Renaissance art (and what was culturally acceptable his contemporaries) by glorifying not simply the beauty of the human trunk, merely past openly celebrating Venus's sexuality. The painting thus completely rejected the asceticism associated with Christian piety during the Middle Ages, suggesting instead a kind of joyful sensuality.

Despite paintings like The Nascency of Venus, still, Botticelli remained a pious Christian throughout his life. In 1490 Botticelli savage under the influence of Girolamo Savonarola, a fiery preacher who came to Florence to denounce its "vanities" (fine art, rich dress, and general worldliness) and call for a strict, even fanatical form of Christian behavior. While at that place is no tangible evidence to support the claim, some stories had it that Botticelli even destroyed some of his own paintings under Savonarola's influence. While Savonarola was executed in 1493, Botticelli did non become on to produce art at the same footstep he had before the 1490s. By and so, of course, he had already clinched his place in art history as one of the major figures of Renaissance painting.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

Da Vinci was famous in his own time equally both one of the greatest painters of his age and as what we would now call a scientist – at the fourth dimension, he was sought after for his skill at applied science, overseeing the construction of the naval defenses of Venice and swamp drainage projects in Rome at different points. He was hired by a whole swath of the rich and powerful in Italia and French republic; in his old historic period he was the official chief painter and engineer of the French king, living in a private chateau provided for him and receiving admiring visits from the king.

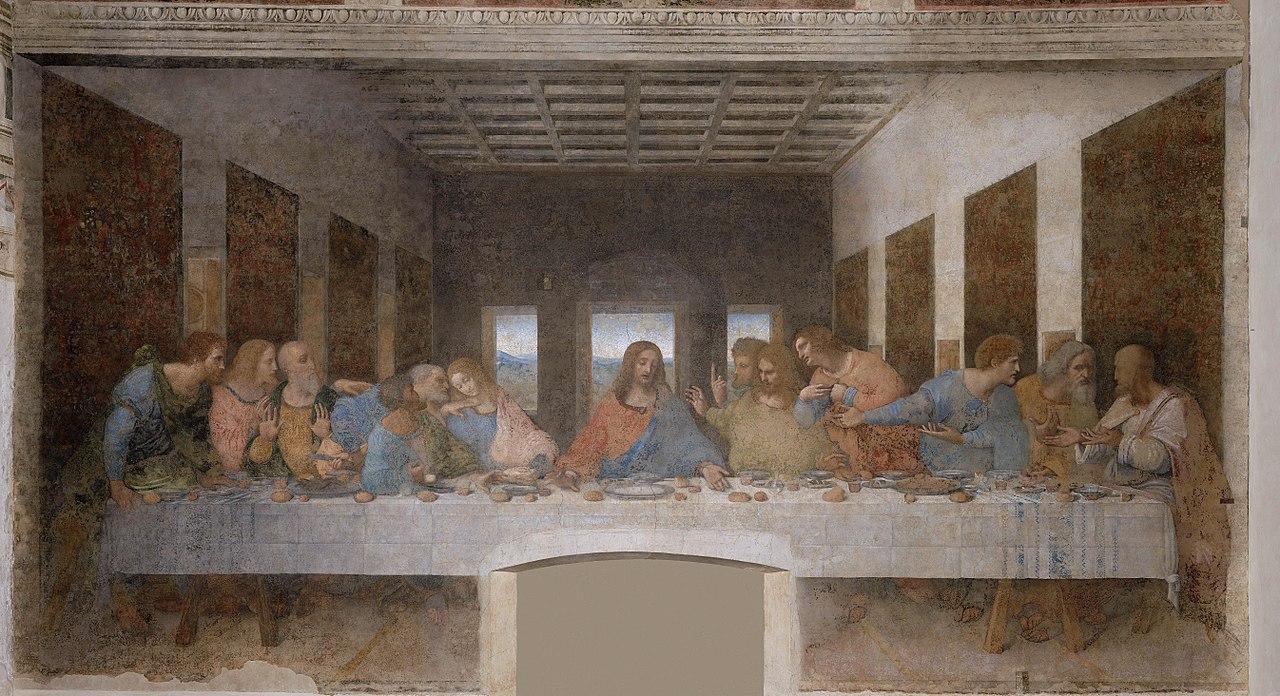

Leonardo Da Vinci's The Last Supper. Note how the walls and ceiling tiles appear to camber downwards toward a point at the horizon behind Jesus (in the middle). That imaginary point – the "vanishing betoken" – was ane of the major artistic breakthroughs associated with linear perspective pioneered by Brunelleschi.

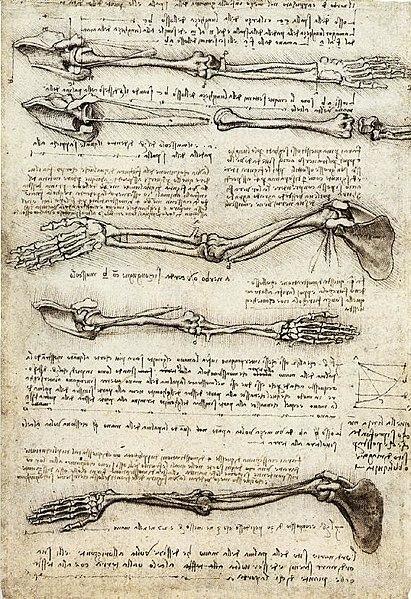

Leonardo's scientific work was often closely related to his creative skills. While the practice of autopsy for medical knowledge was nil new – doctors in the Center East, North Africa, and Europe alike had used autopsies to further medical noesis for centuries – Leonardo was able to document his findings in meticulous detail thanks to his artistic virtuosity. He undertook dozens of dissections of bodies (nearly of them executed criminals) and drew precise diagrams of the parts of the body. He also created speculative diagrams of various machines, from practical designs like hydraulic engines and weapons to fantastical ones like flying machines based on the anatomy of birds.

I of Da Vinci'due south anatomical sketches, in this case examining the skeletal structure of the arm.

Da Vinci is remembered today thanks every bit much to his diagrams of things like flight machines as for his art. Ironically, while he was well known as a practical engineer at the time, no one had a clue that he was an inventor in the technological sense: he never congenital physical models of his ideas, and he never published his concepts, and then they remained unknown until well afterward his death. Also, while his anatomical work anticipated of import developments in medicine, they were unknown during his ain lifetime.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475 – 1564)

Michelangelo was the most historic artist of the Renaissance during his own lifetime, patronized by the urban center council of Florence (run by the Medici) and the pope alike. He created numerous works, most famously the statue of the David and the paintings on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The latter piece of work took him four years of work, during which he argued constantly with the Pope, Julius II, who treated him like an artisan servant rather than the true creative genius Michelangelo knew himself to be. Michelangelo was already the nearly famous artist in Europe thanks to his sculptures. Past the time he completed the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, he had to exist accepted equally one of the greatest painters of his age as well, not simply the single most famous sculptor of the time.

Michelangelo's David, completed in 1504 (it took three years to complete). The statue was meant to celebrate an ideal of masculine beauty, inspired past the case of Greek sculpture and by the work of an earlier Renaissance creative person, Donatello.

In the cease, a biography of Michelangelo written past a friend helped cement the idea that there was an of import distinction between mere artisans and true artists, the latter of whom were temperamental and mercurial just possessed of genius. Thus, the whole idea of the creative person as an ingenious social outsider derives in part from Michelangelo'southward life.

Decision

Renaissance art and scholarship was enormously influential. While the process took many decades, both humanist scholarship and didactics on the one hand and classically-inspired art and compages on the other spread beyond Italian republic over the course of the fifteenth century. By the sixteenth century, the study of the classics became entrenched as an essential part of elite education itself, joining with (or rendering obsolete) medieval scholastic traditions in schools and universities. The beautiful and realistic styles of sculpture and painting spread every bit well, completely surpassing Gothic artistic forms, simply as Renaissance compages replaced the Gothic style of building. Along with the political and technological innovations described in the following chapters, Renaissance learning and art helped bring about the definitive stop of the Centre Ages.

Image Citations (Creative Eatables):

Cosimo de Medici – Public Domain

Printing Press – Graferocommons

Florence Cathedral – Creative Commons, Petar Milošević

Adoration of the Magi – Public Domain, The Yorck Projection

Nascence of Venus – Public Domain

The Final Supper – Public Domain

Da Vinci Anatomical Drawings – Public Domain

The David – Artistic Commons, Jörg Bittner Unna

Source: https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/worldhistory/chapter/chapter-3-the-renaissance/

0 Response to "What Was the Story Behind Thenidea of Culture and Style of Art of Renaissance People"

Postar um comentário