what was done to prevent more casualties on madrid 2004

| 2004 Madrid train bombings | |

|---|---|

| Part of the spillover of the Republic of iraq War and Islamic terrorism in Europe | |

Remains of one of the trains, near Atocha station | |

| Location | Madrid, Spain |

| Engagement | 11 March 2004 (2004-03-11) 07:37 – 07:xl CET (UTC+01:00) |

| Target | Madrid commuter runway network, civilians |

| Assail blazon | Mass murder, fourth dimension bombings, terrorism |

| Weapons | Goma-2 backpack bombs |

| Deaths | 193 |

| Injured | 2,050[ane] |

| Perpetrators | Al-Qaeda in Iraq[2] |

| Motive | Opposition to Spanish participation in the Republic of iraq and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan War |

The 2004 Madrid train bombings (also known in Kingdom of spain equally 11M) were a series of coordinated, nearly simultaneous bombings against the Cercanías commuter train system of Madrid, Spain, on the forenoon of xi March 2004—3 days before Spain's general elections. The explosions killed 193 people and injured around 2,000.[1] [iii] The bombings constituted the deadliest terrorist attack carried out in the history of Espana and the deadliest in Europe since 1988.[iv] The official investigation by the Spanish judiciary found that the attacks were directed past Al-Qaeda in Republic of iraq,[v] [6] allegedly as a reaction to Spain's involvement in the 2003 US-led invasion of Republic of iraq.[seven] [eight] [9] Although they had no role in the planning or implementation, the Spanish miners who sold the explosives to the terrorists were also arrested.[x] [xi] [12]

Controversy regarding the handling and representation of the bombings by the government arose, with Spain'southward two chief political parties — Castilian Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and Partido Pop (PP) — accusing each other of concealing or distorting evidence for electoral reasons. The bombings occurred iii days before general elections in which incumbent José María Aznar's PP was defeated.[13] Immediately later on the bombing, leaders of the PP claimed show indicating the Basque separatist organization ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna) was responsible for the bombings,[14] [xv] while the opposition claimed that the PP was trying to prevent the public from knowing information technology had been an islamist attack, which would exist interpreted every bit the direct issue of Spain'south involvement in Iraq, an unpopular war which the government had entered without the blessing of the Spanish Parliament.[sixteen]

Following the attacks, there were nationwide demonstrations and protests enervating that the government "tell the truth".[17] The prevailing stance of political analysts is that the Aznar administration lost the general elections every bit a result of the treatment and representation of the terrorist attacks, rather than considering of the bombings per se.[eighteen] [19] [20] [21] Results published in The Review of Economic science and Statistics past economist Jose G. Montalvo[22] seem to suggest that indeed the bombings had important balloter impact[23] (turning the electoral issue against the incumbent People's Political party and handing government over to the Socialist Party, PSOE).

After 21 months of investigation, judge Juan del Olmo tried Moroccan national Jamal Zougam, among several others, for his participation conveying out the set on.[24] The September 2007 judgement established no known mastermind nor direct al-Qaeda link.[25] [26] [27] [28] [29]

Description [edit]

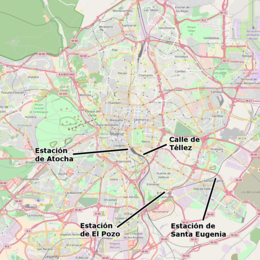

During the tiptop of Madrid rush hour on the morn of Thursday, 11 March 2004, ten explosions occurred aboard four commuter trains (cercanías).[30] The engagement led to the popular abbreviation of the incident as "11-M". All the afflicted trains were traveling on the same line and in the same direction between Alcalá de Henares and the Atocha station in Madrid. It was afterward reported that thirteen improvised explosive devices (IEDs) had been placed on the trains. Flop disposal teams (TEDAX) arriving at the scenes of the explosions detonated two of the remaining three IEDs in controlled explosions, but the 3rd was non found until later in the evening, having been stored inadvertently with luggage taken from one of the trains. The post-obit time-line of events comes from the judicial investigation.[31]

All four trains had departed the Alcalá de Henares station betwixt 07:01 and 07:14. The explosions took identify between 07:37 and 07:forty, as described beneath (all timings given are in local time CET, UTC +one):

- Atocha Station (train number 21431) – Three bombs exploded. Based on the video recording from the station security system, the offset bomb exploded at 07:37, and two others exploded inside iv seconds of each other at 07:38. The wagon affected were the 6th, 5th and fourth. A fourth device was found by the TEDAX team two hours later in the first wagon, which was scheduled to explode when emergency services arrived. Two hours afterwards the first explosions, the bomb was detonated in the offset carriage in a controlled manner.

- El Pozo del Tío Raimundo Station (train number 21435) – At approximately 07:38, only as the train (six wagons and charabanc) was starting to go out the station, two bombs exploded in different carriages. The carriages affected were the fourth and fifth. Another flop was found in the tertiary wagon and was detonated hours later by the TEDAX squad on the platform, slightly damaging the third carriage. Yet another bomb was found in the second carriage; it was disabled hours afterward in the nearby Parque Azorín, and allowed the police to observe several suspects.

- Santa Eugenia Station (railroad train number 21713) – One bomb exploded at approximately 07:38. The only railroad vehicle affected was the fourth.

- Calle Téllez (train number 17305), approximately 800 meters from Atocha Station – Four bombs exploded in different carriages of the train at approximately 07:39. The wagons affected were the beginning, the quaternary, the fifth and 6th. The railroad train was slowing downwardly to stop and expect for train 21431 to vacate platform 2 in Atocha.

At 08:00, emergency relief workers began arriving at the scenes of the bombings. The police reported numerous victims and spoke of 50 wounded and several dead. By 08:30 the emergency ambulance service, SAMUR (Servicio de Asistencia Municipal de Urgencia y Rescate), had prepare a field infirmary at the Daoiz y Velarde sports facility. Bystanders and local residents helped relief workers, as hospitals were told to expect the inflow of many casualties. At 08:43, firefighters reported fifteen dead at El Pozo. Past 09:00, the police had confirmed the death of at least 30 people – twenty at El Pozo and nearly 10 in Santa Eugenia and Atocha. People combed the metropolis's major hospitals in search of family members who they thought were aboard the trains. There were 193 confirmed dead victims, the terminal victim dying in 2014 after having been in a coma for 10 years due to one of the Atocha explosions and not having been able to recover from their injuries.

| Citizenship[32] | Victims |

|---|---|

| | 130 |

| | 16 |

| | 12 |

| | 7 |

| | 7 |

| | 4 |

| | ii |

| | 2 |

| | ii |

| | 2 |

| | ii |

| | 1 |

| | 1 |

| | ane |

| | 1 |

| | 1 |

| | 1 |

| | 1 |

| Full | 193 |

The total number of victims was college than in any other terrorist attack in Spain, far surpassing the 21 killed and 40 wounded from a 1987 bombing at a Hipercor concatenation supermarket in Barcelona. On that occasion, responsibility was claimed by ETA. It was Europe's worst terror attack since the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in December 1988.[4]

Farther bombings spur investigation [edit]

Country funeral at the Almudena Cathedral

A device composed of 12 kilograms of Goma-ii ECO with a detonator and 136 meters of wire (connected to nothing) was found on the track of a high-speed railway line (AVE) on 2 April.[33] The Spanish judiciary chose not to investigate that incident and the perpetrators remain unknown. The device used in the AVE incident was unable to explode because information technology lacked an initiation system.[34]

Before long later on the AVE incident, police force identified an apartment in Leganés, south of Madrid, every bit the base of operations of operations for the individuals suspected of being the perpetrators of the Madrid and AVE attacks. The suspected militants, Sarhane Abdelmaji "the Tunisian" and Jamal Ahmidan "the Chinese", were trapped within the flat by a police raid on the evening of Sabbatum 3 April. At nine:03 pm, when the police force started to assault the premises, the militants committed suicide past setting off explosives, killing themselves and 1 of the police officers.[35] Investigators afterward found that the explosives used in the Leganés explosion were of the same blazon every bit those used in the xi March attacks (though information technology had not been possible to identify a brand of dynamite from samples taken from the trains) and in the thwarted bombing of the AVE line.[33]

Based on the assumption that the militants killed at Leganés were indeed the individuals responsible for the train bombings, the ensuing investigation focused on how they obtained their estimated 200 kg of explosives. The investigation revealed that they had been bought from a retired miner who still had admission to blasting equipment.[36]

Five to 8 suspects believed to be involved in the 11 March attacks managed to escape.[37] In December 2006, the newspaper ABC reported that ETA reminded Castilian Prime Minister Zapatero virtually 11 March 2004 as an instance of what could happen unless the regime considered their petitions (in reference to the 2004 electoral swing), although the source also makes it articulate that ETA 'had nil to do' with the attack itself.[38]

Backwash [edit]

Plaque in retentivity of the casualties in the 11-Thou terror attack in Madrid:

In memory of the victims of the attacks of eleven March 2004, who were transported to the field hospital established here in the Municipal Sports Eye of Daoiz y Velarde. As an expression of sympathy from Madrid's citizens, and of gratitude for the backbone and generosity of all the services and people who came to their aid.

In French republic, the Vigipirate plan was upgraded to orange level.[39] In Italy, the government declared a state of high alarm.[40]

In December 2004, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero claimed that the PP government erased all of the computer files related to the Madrid bombings, leaving only the documents on paper.[41]

On 25 March 2005, prosecutor Olga Sánchez asserted that the bombings happened 911 days later on the 11 September attacks due to the "highly symbolic and qabbalistic charge for local Al-Qaida groups"[42] of choosing that day. Because 2004 was a leap year, 912 days had elapsed betwixt xi September 2001 and 11 March 2004.

On 27 May 2005, the Prüm Convention, implementing inter alia the principle of availability which began to be discussed after the Madrid bombings, was signed past Deutschland, Spain, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Austria, and Belgium.

On 4 January 2007, El País reported that Algerian Ouhnane Daoud, who is considered to exist the mastermind of the eleven-M bombings, has been searching for ways to return to Spain to prepare farther attacks,[43] though this has not been confirmed.[44]

On 17 March 2008, Basel Ghalyoun, Mohamed Almallah Dabas, Abdelillah El-Fadual El-Akil and Raúl González Peña, having been previously found guilty by the Audiencia Nacional, were released after a Higher Court ruling.[45] This courtroom as well verified the release of the Egyptian Rabei Osman al-Sayed.[46]

Responsibility [edit]

On 14 March 2004, Abu Dujana al-Afghani, a purported spokesman for al-Qaeda in Europe, appeared in a videotape claiming responsibility for the attacks.[47]

The Castilian judiciary stated that a loose group of Moroccan, Syrian, and Algerian Muslims and two Guardia Civil and Spanish constabulary informants[48] [49] [50] were suspected of having carried out the attacks. On 11 April 2006, Judge Juan del Olmo charged 29 suspects for their interest in the train bombings.[51]

No bear witness has been found of al-Qaeda involvement,[7] although an al-Qaeda claim was made the solar day of the attacks by the Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades. U.South. officials note that this grouping is "notoriously unreliable".[52] In August 2007, al-Qaeda claimed to be "proud" nigh the Madrid 2004 bombings.[53]

The Independent reported that "Those who invented the new kind of rucksack bomb used in the attacks are said to take been taught in training camps in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, under instruction from members of Morocco'southward radical Islamist Combat Group."[7]

Mohamed Darif, a professor of political science at Hassan II University in Mohammedia, stated in 2004 that the history of the Moroccan Combat Grouping is direct tied to the rise of al-Qaeda in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan. According to Darif, "Since its inception at the terminate of the 1990s and until 2001, the role of the organisation was restricted to giving logistic support to al-Qaeda in Morocco, finding its members places to alive, providing them with fake papers, with the opportunity of marrying Moroccans and with false identities to permit them to travel to Europe. Since 11 September, however, which brought the Kingdom of Morocco in on the side of the fight against terrorism, the organisation switched strategies and opted for terrorist attacks within Morocco itself."[54]

Scholar Rogelio Alonso said in 2007, "the investigation had uncovered a link betwixt the Madrid suspects and the wider world of al-Qaida".[55] Scott Atran said "There isn't the slightest bit of evidence of any relationship with al-Qaida. We've been looking at it closely for years and we've been briefed by everybody nether the dominicus... and goose egg connects them."[56] He provides a detailed timeline that lends credence to this view.[57]

According to the European Strategic Intelligence and Security Center, this is the only extremist terrorist act in the history of Europe where international Islamic extremists collaborated with not-Muslims.[58]

Erstwhile Spanish Prime number Government minister José María Aznar said in 2011 that Abdelhakim Belhadj, leader of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Grouping and current head of the Tripoli Military machine Quango, was suspected of complicity in the bombings.[59] [60]

Allegations of ETA involvement [edit]

Anonymous protest: "The dauntless are brave until the coward wants".

Firsthand reactions to the attacks in Madrid were the several press conferences held by the Castilian prime government minister José María Aznar involving ETA. The Castilian authorities maintained this theory for two days. Because the bombs were detonated three days before the general elections in Spain, the situation had many political interpretations. The United States as well initially believed ETA was responsible,[61] then questioning if Islamic extremists were responsible.[62] Spain's third-largest newspaper, ABC, immediately labelled the attacks as "ETA's bloodiest attack."[63]

Due to the government theory, statements issued shortly after the Madrid attacks, including from lehendakari Juan José Ibarretxe identified ETA every bit the prime suspect, simply the group, which usually claims responsibility for its deportment, denied whatsoever interest.[64] Later testify strongly pointed to the involvement of extremist Islamist groups, with the Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group named as a focus of investigations.[65]

Although ETA has a history of mounting flop attacks in Madrid,[66] the 11 March attacks exceeded any attack previously attempted by a European organisation. This led some experts to point out that the tactics used were more typical of militant Islamic extremist groups, perhaps with a certain link to al-Qaeda, or maybe to a new generation of ETA activists using al-Qaeda every bit a office model. Observers besides noted that ETA customarily, but non ever, issues warnings earlier its mass bombings and that there had been no warning for this assault. Europol manager Jürgen Storbeck commented that the bombings "could have been ETA... Just we're dealing with an attack that doesn't correspond to the modus operandi they have adopted up to now".[67]

Political analysts believe ETA'due south guilt would have strengthened the PP's chances of existence re-elected, as this would have been regarded as the decease throes of a terrorist organisation reduced to desperate measures by the strong anti-terrorist policy of the Aznar assistants.[fourteen] On the other hand, an Islamic extremist attack would have been perceived as the direct event of Spain's involvement in Iraq, an unpopular war that had not been approved by the Castilian Parliament.[16]

Investigation [edit]

All of the devices are thought to have been hidden inside backpacks. The law investigated reports of three people in ski masks getting on and off the trains several times at Alcalá de Henares between 7:00 and 7:10. A Renault Kangoo van was found parked outside the station at Alcalá de Henares containing detonators, sound tapes with Qur'anic verses, and cell phones.[68]

The provincial chief of TEDAX (the bomb disposal experts of the Spanish law) alleged on 12 July 2004 that harm in the trains could non exist caused past dynamite, but past some blazon of armed services explosive, like C3 or C4.[69] An unnamed source from the Aznar assistants claimed that the explosive used in the attacks had been Titadine (used by ETA, and intercepted on its way to Madrid 11 days earlier).[70]

In March 2007, the TEDAX chief claimed that they knew that the unexploded explosive establish in the Kangoo van was Goma-2 ECO the very day of the bombings.[71] He also asserted that "it is incommunicable to know" the components of the explosives that went off in the trains – though he later asserted that it was dynamite. The Judge Javier Gómez Bermúdez replied "I cannot understand" to these assertions.[72]

Test of unexploded devices [edit]

A radio report mentioned a plastic explosive chosen "Special C". Yet, the government said that the explosive establish in an unexploded device, discovered among numberless thought to be victims' lost luggage, was the Castilian made Goma-ii ECO. The unexploded device contained 10 kg (22 lb) of explosive with 1 kg (2.2 lb) of nails and screws packed effectually it every bit shrapnel.[73] In the aftermath of the attacks, nevertheless, the chief coroner alleged that no shrapnel was found in whatsoever of the victims.[74]

Goma-ii ECO was never earlier used by al-Qaeda, but the explosive and the modus operandi were described by The Contained every bit ETA trademarks, although the Daily Telegraph came to the opposite decision.[75]

Ii bombs, one in Atocha and another in El Pozo stations, numbers 11 and 12, were detonated accidentally by the TEDAX. Co-ordinate to the provincial main of the TEDAX, deactivated rucksacks contained some other type of explosive. The 13th bomb, which was transferred to a police force station, contained dynamite, although it did not explode because it was missing two wires connecting the explosives to the detonator. That bomb used a mobile phone (Mitsubishi Trium) equally a timer, requiring a SIM carte du jour to activate the alarm and thereby detonate.[76] The analysis of the SIM carte allowed the police to arrest an alleged perpetrator. On Saturday, xiii March, when three Moroccans and two Pakistani Muslims[77] [78] were arrested for the attacks, it was confirmed that the attacks came from an Islamic grouping.[79] Only one of the 5 persons (the Moroccan Jamal Zougam) detained that day was finally prosecuted.[lxxx]

The Guardia Civil adult an extensive action plan to monitor records corresponding with the utilize of weapons and explosives. In that location were 166,000 inspections conducted throughout the country between March 2004 and November 2004. Nearly ii,500 violations were discovered and over iii tons of explosives, 11 kilometers of detonating cord, and over fifteen,000 detonators were seized.[81]

Suicide of suspects [edit]

Damaged edifice in Leganés where the four terrorists died

On 3 April 2004, in Leganés, south Madrid, iv terrorists died in an apparent suicide explosion, killing ane Grupo Especial de Operaciones (GEO) (Spanish special police assault unit) police officer and wounding 11 policemen. According to witnesses and media, betwixt 5 and eight suspects escaped that 24-hour interval.[37]

Security forces carried out a controlled explosion of a suspicious package found most the Atocha station and subsequently deactivated the two undetonated devices on the Téllez railroad train. A tertiary unexploded device was afterward brought from the station at El Pozo to a police station in Vallecas, and became a central slice of bear witness for the investigation. It appears that the El Pozo bomb failed to detonate considering a prison cell-phone alert used to trigger the flop was set 12 hours tardily.[82]

Conspiracy theories [edit]

Sectors of the People's Party (PP), and certain media, such as El Mundo newspaper and the COPE radio station,[83] go along to support theories relating the attack to a vast conspiracy to remove the governing party from power. Support for the conspiracy was likewise given by the Asociación de Víctimas del Terrorismo (AVT), Spain's largest clan of victims of terrorism.

These theories speculate that ETA and members of the security forces and national and foreign (Morocco) hugger-mugger services were involved in the bombings.[84] [85] Defenders of the claims that ETA participated in some form in the 11 March attacks have affirmed that there is circumstantial evidence linking the Islamic extremists with 2 ETA members who were detained while driving the outskirts of Madrid in a van containing 500 kg of explosives 11 days before the train bombings.[86] The Madrid judge Coro Cillán is continuing to hear conspiracy theory cases, including one accusing authorities officials of ordering the scrapping of the bombed railroad train cars in order to destroy evidence.[87]

Invasion of Iraq policy [edit]

The public seemed convinced that the Madrid Bombings were a result of the Aznar government's alignment with the U.S. and its invasion of Iraq. The terrorists backside the 11-G attack were somewhat successful because of the election outcome. Before the attack, the incumbent Pop Party led the polls by 5 percent. It is believed that the Popular Political party would accept won the election if information technology had not been for the terrorist attack. The Socialist Party, led past José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, ended upwards winning the ballot by 5%. The Socialist Party had called for the removal of Spanish troops from Iraq during its campaigning. Zapatero promised to remove Spanish troops by 30 June 2004, and the troops were withdrawn a month earlier than expected. Xx-eight percent of voters said that the bombings influenced their opinions and vote. An estimated ane 1000000 voters switched their vote to the Socialist Party after the Madrid bombings. These voters who switched their votes were no longer willing to support the Popular Political party'southward stance on state of war policy. The bombings besides influenced 1,700,000 citizens to vote who did not plan on originally voting. On the other hand, the terrorist attacks discouraged 300,000 people from voting. Overall, at that place was a net four percent increase in voter turnout.[88]

Trial [edit]

Judge Juan del Olmo found "local cells of Islamic extremists inspired through the Internet" guilty for the 11 March attacks,[89] not Armed Islamic Group or Moroccan Islamic Combatant Grouping. These local cells consist of hashish traffickers of Moroccan origin, remotely linked to an al-Qaeda cell that had been already captured. These groups bought the explosives (dynamite Goma-2 ECO) from low-level thieves, police force and Guardia Civil informers in Asturias using money from the pocket-sized-scale drug trafficking.[xc]

Co-ordinate to El Mundo, "the notes found on the Moroccan informer 'Cartagena' prove that the Law had the leaders of the cell responsible for the xi March attacks under surveillance." Yet, none of the notes refer to the preparation of whatsoever terrorist attack.[91]

The trial of 29 defendants began on fifteen February 2007. According to El País, "the Courtroom dismantled one by one all conspiracy theories" and demonstrated that whatever link with or interest in the bombings by ETA was either misleading or groundless. During the trial the defendants retracted their previous statements and denied whatsoever involvement.[92] [93] [94] According to El Mundo the questions of "by whom, why, when and where the Madrid train attacks were planned" are withal "unanswered", because the alleged masterminds of the attacks were acquitted. El Mundo also claimed -amid other misgivings[95] [96] [97]- that the Spanish judiciary reached "scientifically unsound" conclusions about the kind of explosives used in the trains,[98] and that no direct al-Qaeda link was found, thus "debunking the key statement of the official version".[99] Anthropologist Scott Atran described the Madrid trial every bit "a complete farce" pointing out the fact that "There isn't the slightest scrap of evidence of any operational relationship with al-Qaida". Instead, "The overwhelming majority of [terrorist cells] in Europe accept nothing to do with al-Qaida other than a vague human relationship of ideology."[55]

Though the trial proceeded smoothly in its opening months, 14 of the 29 defendants began a hunger strike in May, protesting against the allegedly "unfair" office of political parties and media in the legal proceedings. Judge Javier Gómez Bermúdez refused to suspend the trial despite the strike, and the hunger strikers ended their fast on 21 May.[100]

The last hearing of the trial was held on 2 July 2007. Transcripts and videos of the hearings tin be seen on datadiar.tv.[101]

On 31 October 2007, the Audiencia Nacional of Espana handed down its judgements. Of the 28 defendants in the trial, 21 were institute guilty on a range of charges from forgery to murder. Two of the defendants were sentenced each to more than forty,000 years in prison.[102] [103]

Constabulary surveillance and informants [edit]

In the investigations carried out to discover out what went incorrect in the security services, many individual negligences and miscoordinations betwixt different branches of the constabulary were found. The group dealing with Islamist extremists was very minor and in spite of having carried out some surveillances, they were unable to stop the bombings. Also, some of the criminals involved in the "Little Mafia" who provided the explosives were constabulary informants and had leaked to their case officers some tips that were not followed upward on.

Some of the alleged perpetrators of the bombing were reportedly nether surveillance by the Spanish law since 2001.[104] [105] [106]

At the time of the Madrid bombings, Spain was well equipped with internal security structures that were, for the nearly part, effective in the fight confronting terrorism. It became evident that there were coordination problems between law forces likewise every bit within each of them. The Interior Ministry building focused on correcting these weaknesses. It was Spain's goal to strengthen its police intelligence in order to bargain with the risks and threats of international terrorism. This determination for the National Police and the Guardia Civil to strengthen their counter-terrorism services, led to an increase in jobs aimed at preventing and fighting global terrorism. Counter-terrorism services increased its employment by nearly 35% during the legislature. Homo resources in external information services, dealing with international terrorism, grew past 72% in the National Constabulary force and 22% in the Guardia Civil.[107]

Controversies [edit]

The authorship of the bombings remains a controversial issue in Spain. Sectors of the Partido Popular (PP) and some of the PP-friendly media outlets (primarily El Mundo and the Libertad Digital radio station) claim that there are inconsistencies and contradictions in the Spanish judicial investigation.

Equally Castilian and international investigations proceed to merits the unlikeliness of ETA'south active implication, these claims have shifted from straight accusations involving the Basque separatist organisation[108] to less specific insinuations and general scepticism.[109] Additionally, there is controversy over the events that took place between the bombings and the general elections held iii days later.[110] [111]

Reactions [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You tin can assistance by adding to it. (Nov 2015) |

In the backwash of the bombings, at that place were massive street demonstrations across Kingdom of spain to protest against the train bombings.[112] The international reaction was as well notable, every bit the calibration of the assail became clearer.

Memorial service for victims [edit]

A memorial service for the victims of this incident was held on 25 March 2004 at the Almudena Cathedral. It was attended past King Juan Carlos I, Queen Sofía, victims' families, and representatives from numerous other countries, including British prime minister Tony Blair, French president Jacques Chirac, German language chancellor Gerhard Schröder, and U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell.[113]

See also [edit]

Specifically nearly the 2004 Madrid bombings [edit]

- Atocha station memorial

- Brandon Mayfield, wrongfully identified via fingerprints

- Casualties of the 2004 Madrid bombings

- Controversies nearly the 2004 Madrid train bombings

- Forest of Remembrance

- Reactions to the 2004 Madrid train bombings

- José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero

- 2004 Madrid railroad train bombings suspects

- Rabei Osman

Other [edit]

- List of terrorist incidents involving railway systems

- 2000 Madrid bombing

- February 2004 Moscow Metro bombing, a very similar set on barely five weeks before.

- 2006 Madrid–Barajas Airport bombing

- xi July 2006 Bombay train bombings

- 7 July 2005 London bombings

- 2006 German train bombing attempts

References [edit]

- ^ a b "El automobile de procesamiento por el 11-M - Documentos" [The automated processing for 11-Grand - Documents]. El Mundo (in Castilian). 11 April 2006.

- ^ El País

- ^ ZoomNews (in Spanish). The 192nd victim (Laura Vega) died in 2014, after a decade in coma in a infirmary of Madrid. She was the terminal hospitalized injured person.

- ^ a b Paul Hamilos; Marking Tran (31 October 2007). "21 guilty, seven cleared over Madrid train bombings". The Guardian . Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Castilian Indictment on the investigation of 11 March". El Mundo (in Castilian). Spain. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ O'Neill, Sean (15 February 2007). "Spain furious as U.s.a. blocks admission to Madrid bombing 'primary'". The Times. London, U.k.. Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

The al-Qaeda leader who created, trained and directed the terrorist cell that carried out the Madrid train bombings has been held in a CIA "ghost prison" for more than a yr.

- ^ a b c Elizabeth Nash (vii November 2006). "Madrid bombers 'were inspired by bin Laden address'". The Contained. Uk. Archived from the original on six July 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

While the bombers may have been inspired past bin Laden, a two-twelvemonth investigation into the attacks has found no evidence that al-Qa'ida helped plan, finance or carry out the bombings, or fifty-fifty knew nearly them in advance. Ten bombs in backpacks and other small numberless, such equally gym bags, exploded. One flop did non explode and was defused. The police did controlled explosions on 3 other bombs.

- ^ "Trial Opens in Madrid for Train Bombings That Killed 191". KABC-Telly Los Angeles. xv February 2007. Archived from the original on thirteen November 2013.

The cell was inspired by al-Qaida but had no straight links to it, nor did it receive financing from Osama bin Laden's terrorist organization, Castilian investigators say

- ^ "Al Qaeda, Madrid bombs not linked: Castilian probe". Toronto Star. 9 March 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007 – via borrull.org.

- ^ "Islam and terrorism". International Found for Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on four June 2011. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ Javier Jordán; Robert Wesley (nine March 2006). "Terrorism Monitor | The Madrid Attacks: Results of Investigations Ii Years Later on". 4 (5). Jamestown Foundation.

- ^ "Madrid: The Backwash: Kingdom of spain admits bombs were the piece of work of Islamists". The Independent. London, UK. 16 March 2004. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- ^ "Archived re-create" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2004. Retrieved 16 Dec 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Lago, I. (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) Del 11-M al 14-M: Los mecanismos del cambio balloter, pp. 12–13. Archived 23 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Selected bibliography on political analysis of the 11-Chiliad aftermath". El Mundo. Spain. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ a b 92% of the Spanish population expressed its disagreement with the intervention Clarin.com, 29 March 2003.

- ^ Cf. Meso Ayeldi, K. "Teléfonos móviles east Internet, nuevas tecnologías para construir united nations espacio público contrainformativo: El ejemplo de los wink mob en la tarde del 13M" Universidad de La Laguna Archived 19 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; accessed 1 June 2018.

- ^ El Periódico – 11MArchived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ El Periódico – 11MArchived xviii Apr 2009 at the Wayback Car

- ^ El Periódico – 11MArchived 18 Apr 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Madrid Bombings and U.Due south. Policy – Brookings". Brookings.edu. 31 March 2004. Archived from the original on vi June 2011. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ "José García-Montalvo". 30 June 2015.

- ^ Montalvo, José G. (2011). "Voting Later the Bombings: A Natural Experiment on the Upshot of Terrorist Attacks on Autonomous Elections". The Review of Economic science and Statistics. 93 (four): 1146–1154. doi:x.1162/REST_a_00115. JSTOR 41349103. S2CID 57571182.

- ^ "Del Olmo sólo tiene ya united nations presunto autor material del xi-M para sentar en el banquillo". El Mundo. Spain. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ Barrett, Jane (31 October 2007). "The biggest surprise was that two men originally accused of planning the assail were convicted only of belonging to a terrorist group, not of the Madrid killings... 'Nosotros're very surprised past the acquittal,' said Jose Maria de Pablos, attorney of a victims' association linked to conspiracy theories. 'If it wasn't them, nosotros take to find out who information technology was. Somebody gave the order.'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ "ETA, Irak, Zougam, el explosivo... y otras claves de la sentencia del 11-Grand". El Mundo. Spain. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved five May 2011.

- ^ "El 11-M se queda sin autores intelectuales al quedar absueltos los tres acusados de serlo". El Mundo. Espana. 31 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "El final del principio en la investigación del 11-K". El Mundo. Espana. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ "El tribunal del 11-Thousand desbarata la tesis clave de la versión oficial en su sentencia". El Mundo. Spain. 31 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Audio of the 2d wave of bombs recorded in a cellular phone conversation Archived 5 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Judicial Indictment – Downloadable in Spanish

- ^ 20minutos.es (11 March 2012). "¡11-G Masacre en Madrid. viii Años Despues! (Recordando a las Victimas)". Listas - 20Minutos.

- ^ a b The Terror Web (The New Yorker) Archived 11 February 2007 at the Wayback Car

- ^ "Archivan las investigaciones sobre el intento de atentado contra el AVE". Libertaddigital.com. 26 Nov 2008. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Goodman, Al (4 Apr 2004). "Suspected Madrid bombing ringleader killed". CNN.

- ^ "Madrid flop cell neutralised (BBC Europe)". BBC News. 14 Apr 2004. Retrieved five May 2011.

- ^ a b "Madrid bombing suspects". BBC News. 10 March 2005. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ "La banda recordó al Ejecutivo el precedente del 11-One thousand" [The group reminded the Executive of the precedent of eleven-M]. ABC (in Castilian). 31 December 2006. Archived from the original on 2 Jan 2007.

- ^ "France raises alert to orange". BBC News. 12 March 2004. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ The Terrorist Threat to the Italian Elections (Jamestown) Archived 19 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Aznar "wiped files on Madrid bombings"". The Guardian. 14 December 2004 – via El País.

- ^ Un factor "cabalístico" en la elección de la fecha de la matanza en los trenes, "El País", 2005 March ten

- ^ El País El argelino huido tras perpetrar el xi-M preparaba nuevos atentados en España El País, 4 January 2007

- ^ Metronieuws.nlArchived five Dec 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guillermo Peris Peris (17 July 2008). "El TS absuelve a cuatro procesados del 11-M por falta de pruebas y un error en un registro ordenado por Del Olmo". Diario Siglo XXI. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ^ "Tribunal Supremo concluye vista de recursos contra sentencia atentados 11-One thousand". ADN.es. 2 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved ane September 2009.

- ^ "Full text: 'Al-Qaeda' Madrid claim". BBC News. 14 March 2004. Retrieved eighteen January 2008.

- ^ The Times Flop squad link in Castilian blast

- ^ Rafá Zouhier was a confidante of the Guardia Civil earlier, during and after the bombings... José Emilio Suárez Trashorras was also a police force confidante -Rafá Zohuier era confidente de la Guardia Civil antes, durante y después de los atentados... José Emilio Suárez Trashorras... También era confidente de la policía-

- ^ "The two key collaborators of the Madrid railroad train bombings were police force confidantes"

- ^ "Suspects indicted in Madrid railroad train attacks (OnlineNewsHous)". Pbs.org. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Francie Grace (11 March 2004). "CBS News. Madrid Massacre Probe Widens". CBS News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Al Qaeda dice sentirse 'orgullosa' de la destrucción que afectó a Madrid el 11-M". El Mundo. Spain. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Mohamed Darif (30 March 2004). "The Moroccan Combat Group (PDF)" (PDF). Existent Instituto Elcano. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 16 Feb 2010.

- ^ a b "The worst Islamist attack in European history". The Guardian. London, UK. 31 October 2007. Retrieved five May 2011.

- ^ Paul Hamilos; Mark Tran (31 October 2007). "21 guilty, seven cleared over Madrid train bombings". The Guardian. Madrid. Retrieved five May 2011.

- ^ Jason Shush (24 October 2010). "Talking to the Enemy by Scott Atran – A Review by Jason Burke". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ PDFArchived 10 October 2006 at the Wayback Automobile"Until now, in that location has never been any instance of a terrorist action by international Islamist made in collaboration with not-Muslims." French original: Il n'y a d'ailleurs à ce jour aucun case d'une action terroriste menée par des islamistes internationalistes en collaboration avec des non-musulmans

- ^ José María Aznar (9 December 2011). "Spain's Sometime Prime Government minister José María Aznar on the Arab Awakening and How the West Should React". CNBC Guest Weblog . Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Dore Golden (fourteen December 2011). "Diplomacy afterward the Arab uprisings". The Jerusalem Post . Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "cable 04MADRID827". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on xv December 2010.

- ^ "cablevision 04MADRID893". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010.

- ^ "ETA comete el atentado más sangriento de su historia" [ETA commits the bloodiest assail in its history]. ABC (in Castilian). eleven March 2004.

- ^ Francie Grace (15 March 2004). "Voters Oust Spanish Regime". CBS News. Archived from the original on 8 Nov 2015.

On Sunday, a Basque-language daily published a argument by ETA in which the group for a second time denied interest in the attacks

- ^ "Madrid bombings: Defendants". BBC News. 17 July 2008. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ Francie Grace (11 March 2004). "Madrid Massacre Probe Widens". CBS News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Ewen MacAskill; Richard Norton-Taylor (12 March 2004). "From Bali to Madrid, attackers seek to inflict ever-greater casualties". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Kingdom of spain Campaigned to Pin Blame on ETA". The Washington Postal service. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on viii February 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Los TEDAX revisaron "dos veces" todos los vagones del 11-G sin encontrar Goma two ni la mochila de Vallecas (Libertad Digital)Archived 28 Apr 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CBS News: Madrid Massacre Probe Widens. Madrid, eleven March 2004 "The bombers used Titadine, a kind of compressed dynamite also found in a bomb-laden van intercepted final month as it headed for Madrid, a source at Aznar's part said, speaking on status of anonymity. Officials blamed ETA so, too."

- ^ "El 11M se supo que el explosivo era Goma 2 ECO" [The 11M learned that the explosive was Goma 2 ECO]. ABC (in Spanish). 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on nine Dec 2008.

- ^ "El ex jefe de Tedax reconoce que sus análisis dejaron 'interrogantes' sobre el explosivo" [The erstwhile head of Tedax acknowledges that his analysis left 'questions' about the explosive]. El Mundo (in Castilian). Spain. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on vi June 2011. Retrieved v May 2011.

- ^ "News". The Telegraph. 15 March 2016. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Ni clavos, ni tuercas, ni tornillos; no había metralla entre nuestros 191 muertos". Libertaddigital.com. Archived from the original on xv July 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Madrid: The Backwash: Kingdom of spain admits bombs were the work of Islamists "For the first time in its history al-Qa'ida has used not the inexpensive and archaic fertiliser-based bombs familiar in attacks from Yemen to Istanbul, but Goma 2 ECO gelignite, detonated by mobile phones. This sophisticated twin technique has previously been the trademark of ETA, the Basque separatist group." [ expressionless link ]

- ^ La Policía encuentra una decimotercera mochila bomba en la comisaría de Puente de Vallecas (El Mundo)

- ^ El Mundo

- ^ Libertad digital, los enigmas del xi-Thou half-dozen. Las primeras detenciones Las detenciones de los hindúes

- ^ Al Qaeda reivindica los atentados en united nations vídeo hallado en Madrid (El Mundo)

- ^ El Mundo

- ^ (Reinares, 2009, 377)

- ^ Ghosh, Aparisim (fourteen March 2004). "A Strike at Europe's Heart". Fourth dimension. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Espana's 11-M and the right's revenge Archived 23 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Open Democracy)

- ^ Zaplana claims PSOE "afraid that the truth will come up out", The Spain Herald, xxx March 2005. Recovered from the Cyberspace Annal.

- ^ Los agujeros negros del xi-M El Mundo, 19 Apr 2004. Article defending a number of conspiracy theories related to the bombings.

- ^ Madrid: The Aftermath: Kingdom of spain admits bombs were the work of Islamists "Connections have besides been drawn between the drivers of a van establish on the outskirts of Madrid on 29 February containing 500 kg of explosive and the Islamists: the two men in the van are declared to be members of ETA, and also to have been amongst a group of Basques who expressed strong support for Iraq against the Anglo-American invasion. Just so far the show does not go beyond the circumstantial." Retrieved 1 September 2009. Archived 4 September 2009.

- ^ El País 31 Jan 2012 edition (Madrid newspaper)

- ^ (Abrahms 2007, p. 186)

- ^ El auto de procesamiento por el 11-M (El Mundo)

- ^ Crumley, Bruce (13 March 2005). "Across the Split up". Time. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Las notas del confidente marroquí 'Cartagena' prueban que la Policía controlaba a la cúpula del 11-Grand (El Mundo)

- ^ Comienza en Madrid el juicio por el mayor atentado islamista registrado en Europa, El País, 15 February 2007

- ^ El Morabit niega ahora haber sido avisado de los atentados del xi-K, El Mundo, 20 February 2007

- ^ "Madrid bombing 'mastermind' protests innocence", fifteen February 2007, 1:59 pm ET Agence France-Presse, MyWire.com

- ^ ETA, Irak, Zougam, el explosivo... y otras claves de la sentencia del 11-M

- ^ El 11-Chiliad se queda sin autores intelectuales al quedar absueltos los tres acusados de serlo

- ^ Guía para abordar la sentencia del 11-M

- ^ El final del principio en la investigación del 11-Grand

- ^ El tribunal del 11-G desbarata la tesis clave de la versión oficial en su sentencia

- ^ The Madrid bombing trial blog Madrid11.net [ dead link ]

- ^ "Transcripts and videos of the Madrid trial". Datadiar.tv. Archived from the original on sixteen February 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Jane Barrett (31 October 2007). "Court finds 21 guilty of Madrid bombings". Reuters . Retrieved 31 Oct 2007.

- ^ James Sturcke (31 Oct 2007). "List of sentenced defendants". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Spain: State Funeral For Madrid Bombing Victims Gathers World Leaders" Radio Gratis Europe/Radio Freedom: "The primary doubtable remains Moroccan Jamal Zougam, who allegedly had close ties to Islamist militants and who has been under watch by Castilian, French, and Moroccan agents since 2001"

- ^ "Spanish investigators confident"Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine "The atomic number 82 suspect is Jamal Zougam, who allegedly has close ties with Islamist militants and has been under watch by Spanish, French and Moroccan agents since 2001 at least."

- ^ "Un inspector asegura que perseguían a varios de los acusados desde enero de 2003" [An inspector assures that several defendant were being pursued since January 2003]. ABC (in Spanish). 21 March 2007. Archived from the original on 25 September 2007.

- ^ (Reinares, 2009, 371)

- ^ El MundoArchived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ "Las tesis poco claras de la fiscalía en sus conclusiones sobre el 11-M". El Mundo.

- ^ Giles Tremlett (xv September 2006). "Newspaper spat over Madrid bombs 'conspiracy'". The Guardian.

- ^ "Castilian Terrogate". nationalreview.com. National Review.

- ^ "Bombs were Spanish-made explosives | Millions pack Madrid's streets". CNN. 13 March 2004.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (25 March 2004). "World Leaders Converge in Spain to Mourn Bomb Victims". The New York Times . Retrieved 27 August 2020.

External links [edit]

- BBC News In Depth

- Was the effort plotted in Mohammed VI's Château?

- U.N. Security Council Resolution 1530

Coordinates: 40°24′24″North three°41′22″West / 40.40667°N 3.68944°W / forty.40667; -three.68944

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2004_Madrid_train_bombings

0 Response to "what was done to prevent more casualties on madrid 2004"

Postar um comentário